The life of Dona Isabel de Solís, a Spanish noblewoman, is a fascinating tale of love, power, and intrigue that spans the 17th century. Born into a prominent family, she was destined for greatness, and her story is a testament to the complexities of the Spanish aristocracy during that era.

From her early years as a member of the royal court to her later years as a powerful matriarch, Dona Isabel de Solís navigated the treacherous waters of Spanish politics with ease, earning her a reputation as a shrewd and cunning strategist. Her life is a remarkable example of the influence women could wield in a society dominated by men, and her legacy continues to captivate historians and scholars to this day.

what is the life story of dona

The life story of Dona Isabel de Solís is a fascinating and complex tale that spans across the 15th and 16th centuries. Born in Castile, Spain, she was initially a Christian noblewoman from a prominent family. However, her life took a dramatic turn when she was captured during a raid on Castile by the Kingdom of Granada in 1471. She was sold into slavery and eventually became the concubine of Abu l-Hasan Ali, the Sultan of Granada. Under the name Zoraya, she converted to Islam and gained significant influence over her spouse. She bore him two sons, Nasr and Said, who were recognized as royal princes. However, her marriage to the Sultan was met with opposition from his first wife, Aixa, who was a descendant of the Prophet Mohammed. This led to a civil war in Granada in 1482. After the Sultan's deposition, Dona Isabel was taken captive by Aixa's faction and was allowed to live on condition that the Sultan give up the throne to his son Boabdil. Later, when the Sultan retook the throne, he was succeeded by his brother Muhammad XIII of Granada (El Zagal), who abdicated in favor of Boabdil in 1486. Dona Isabel and her sons became wards of El Zagal, and she chose to remain in Granada after El Zagal left for North Africa in 1491. Following the defeat of Granada in 1492, Dona Isabel and her sons attracted the attention of Ferdinand and Isabella. She initially remained a Muslim under the name Zoraya but eventually converted back to Catholicism, taking back her original name Isabel, and became known as Isabel de Granada and Queen Isabel. She is last mentioned living in Seville in 1510. Dona Isabel's life is a testament to the complexities of the Spanish aristocracy during the 15th and 16th centuries, as well as the significant influence women could wield in a society dominated by men. Her story has been immortalized in historical fiction and drama, reflecting her enduring impact on the historical record.what is the origin of the name dona

The origin of the name "Dona" is complex and multifaceted. It has multiple roots and meanings across different languages and cultures. Here's a breakdown of the various origins mentioned in the provided sources: Italian Origin: The name "Dona" is derived from the root name "Donna," which means "lady" or "woman." It is used as a feminine form of Donald, meaning "world ruler," or as a borrowing from the Italian "donna," meaning "lady". Spanish Origin: The term "dona" is also used in Spanish, where it is derived from the Latin "domina," meaning "lady" or "mistress." This origin is mentioned in the context of the historical figure Dona Isabel de Solís, who was a Spanish noblewoman. Italian Family Crest: The surname "Dona" originated in the Papal States of Italy and is characterized by its patronymic and local roots. The earliest recorded bearer of the name lived in Assisi in 1160 and was part of the Guelph faction. Hungarian Origin: In Hungarian, "Dona" is a pet form of the personal name Donát, which is derived from the Latin "Dominus," meaning "master". Catalan Origin: In Catalan, "Dona" is a surname derived from a pet form of the personal name Donat, which is also related to the Latin "Dominus". In summary, the name "Dona" has multiple origins across different languages and cultures, including Italian, Spanish, Hungarian, and Catalan. Each origin reflects the name's evolution and adaptation in various contexts, often tied to meanings related to nobility, power, or femininity.what are some famous people named dona

Some famous people named Dona include: Dona Drake: A black actress, singer, and dancer who was famous in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. She was known for her roles in movies such as "Road to Morocco" (1942), "So This Is New York" (1948), "The Girl from Jones Beach" (1949), and "Beyond the Forest" (1949). Gracia Mendes Nasi: A Jewish woman who played a significant role in the history of the Ottoman Empire. She was a prominent figure in the court of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and was known for her influence and strategic abilities. These individuals demonstrate the diverse range of notable individuals who have borne the name Dona across different cultures and professions. |

| Maria Luisa, Duquesa de Sevilla, in 1920. Photo (c) National Portrait Gallery. |

Born at 1pm on 4 April 1868 at Madrid, María Luisa Enriqueta Josefina de Borbón y Parade was the first of three daughters of Enrique Pío de Borbón y Castellví, 2nd Duke of Seville (1848-1894) and Josefina Parade y Sibié (1840-1939). María Luisa's parents wed two years after her birth on 5 November 1870 at Pau, France; the marriage of her father and mother legitimised María Luisa. According to the text of a later lawsuit, it was posited that Enrique and Josefina waited to marry and disclose the existence of María Luisa, who had always lived with her parents, until after the death of María Luisa's paternal grandfather, Don Enrique María de Borbón, 1st Duke of Seville, in a duel with the Duke of Montpensier on 12 March 1870.

|

| María Luisa's grandfather Enrique with his four sons, the eldest being María Luisa's father. |

The paternal grandparents of María Luisa were Enrique María de Borbón (Infante of Spain from 1823-1848 and then from 1855-1867), 1st Duke of Seville (1823-1870), and Elena de Castellvi y Shelly-Fernandez de Cordova (1821-1863). María Luisa's maternal grandparents were Jean Parade and Geneviève Sibié. María Luisa's paternal great-uncle was King Consort Francisco de Asis of Spain, the husband of Queen Isabel II of Spain, and putative father of King Alfonso XII of Spain.

|

| María Luisa's father: Enrique, 2nd Duque de Sevilla. |

María Luisa was followed by two younger sisters: Marta de Borbón y Parade (1880-1928) and Enriqueta de Borbón y Parade (1888-1967; married her first cousin Francisco de Borbón). For unknown personal and warped reasons, Josefina held a great disdain for her eldest daughter, María Luisa, and showed a marked preference for her second daughter, Marta, the first of Josefina's children born after she married Enrique. On the other hand, Enrique reportedly loved all of his daughters the same and, understandably, believed that his eldest daughter María Luisa should succeed him to the Ducado de Sevilla, while Josefina showed preference their second daughter Marta. King Alfonso XII of Spain felt concerned enough about the treatment of María Luisa by her mother that he had his cousin enrolled at the Colegio Santa Isabel in Madrid. María Luisa had initially expressed a desire to enter religious orders, which met with approval from her mother Josefina, as such a move would guarantee that María Luisa would not succeed her father to the Duchy of Seville, and thus pave the way for Josefina's preferred daughter Marta to become the Duchess. When Enrique's last and youngest daughter, Enriqueta, was born on 28 June 1885, the Duke of Seville took his eldest daughter out of school and became to introduce her to society, as he was now certain that María Luisa would very likely follow him to the Seville title. Josefina's meanness towards her seventeen year-old daughter accelerated after María Luisa left Colegio Santa Isabel to such an extent that after the family had gone on a vacation together during the summer of 1885, that when María Luisa had returned to Madrid, then the young woman make the decision to try to join a religious order, so as to escape from her mother's cruelty. Under the protection of Queen Regent Maria Cristina and King Francisco de Asis, María Luisa then went to an establishment in Lourdes accompanied by a nun of the same order that ran the Colegio Santa Isabel. Maria Cristina and her father-in-law Francisco paid María Luisa's fees at the institution in Lourdes; María Luisa was eventually compelled leave her noviciate owing to illness. From there, she moved to London where she lived at a Convent of the Assumption in Kensington Square, where she resided until her eventual marriage.

Enrique, 2nd Duke of Seville, died on 12 July 1894 while on a ship in the Red Sea. A few weeks after her father's death, María Luisa married Juan Lorenzo Francisco Monclús y Cabanellas (1862-1918) on 25 July 1894 in London. Juan was the son of Francisco Monclús and Dolores Cabanellas.

On 12 September 1894, Josefina, Dowager Duchess of Seville, filed a lawsuit contesting that (1) María Luisa should not be allowed to succeed her father as Duchess of Seville, (2) that María Luisa's sister Marta should succeed to the dukedom, (3) that María Luisa should not receive any part of her father's estate, and (4) that Marta and Enriqueta should be the sole heiresses of the late duke. On 15 December 1894, the court ruled that all three daughters of Enrique, Duke of Seville, were entitled to equal shares of his estate. On 15 July 1895, María Luisa was legally acknowledged as the 3rd Duchess of Seville by the Ministry of Justice and by royal decree.

The persecution of the daughter by mother did not cease. In March 1896, the Dowager Duchess of Seville brought another lawsuit wherein Josefina sought to completely destroy María Luisa's position. In her suit, Josefina asked that the courts nullify the judgement of 15 December 1894 in addition to declaring void the baptismal certificate of María Luisa. The desire of Josefina was to have her eldest daughter declared to be not only illegitimate, but also to allege that her eldest daughter was not the daughter of her late husband Enrique. The ultimate aim of Josefina's actions were to guarantee that her second daughter Marta would become the Duchess of Seville.

The claims of Josefina, Dowager Duchess of Seville, were sensational and extraordinary. Josefina denied that she had given birth to a daughter on 4 April 1868 (her eldest daughter's date of birth) in Madrid. She claimed that she was still living in France, her country of birth, at the time. Josefina claimed that María Luisa had been born on 4 April 1863 in Paris, and that Enrique could not have been her father, as he was only fourteen years-old at the time. Josefina asserted that she and Enrique, after their 1870 marriage, had allowed María Luisa to adopt the Borbón surname; however, Josefina stated that the couple had only done this being mindful of the supposedly sad circumstances of the young girl, who had no other family. Josefina introduced into evidence letters allegedly from her late husband, in which Enrique claimed to only have two legitimate daughters, Marta and Enriqueta, and letters allegedly from María Luisa in which her daughter wrote that she had no claim to the Dukedom of Seville or to the personal fortune of Enrique. One of the letters provided read as follows: "Being ignorant of the lot that Providence has in store for me, and as it may be possible that my days are numbered, in order to safeguard the interests and rights of my beloved and unfortunate daughters Marta de Borbón and Enriqueta de Borbón, who are my only daughters and are legitimate, I entrust this writing to my beloved wife, Josefina Paradé y Libié, Duchess of Sevilla, so that upon my death she may defend the rights of the two beings whom I love so much.-Having had no children during the first years of our marriage and believing that, considering the time elapsed, we would never enjoy that happiness, at the request of my wife I decided to bestow my name upon and to have considered as my daughter a girl whom my wife had sheltered, who stayed in Paris under the name of María Paradé at the Bohnier boarding school and under the name of María Sevilla at the boarding school of Madame Jourdani and under the latter name in another school of Angulema until the day when she first bore my name, being thereafter considered as our daughter. Providence having been so kind as to give me on May 5, 1880, my adored daughter Marta and on June 28, 1885, my other much beloved daughter Enriqueta, the situation of my legitimate daughters, my true and only daughters, was critical in the face of the claims of the girl to whom, out of pity, I had given my name and by which she is known in the Royal College of Santa Isabel (Madrid); and although in a moment of folly I acknowledged her, I can not ignore the duty of a loving father, the voice of blood and of conscience, or the right that my real daughters have, so that nobody may claim what is theirs and so that they may know the truth.” This letter of Enrique, Duke of Seville, was later used in a case that appeared before the Supreme Court in Puerto Rico in which a man sought the annulment of his acknowledgement of a natural child.

Josefina's assertions were met with a declaration by the civil servant who authorised the baptism of her eldest daughter. The statement read: "In the city of Madrid, on 9 March 1878, I, Dr. Vicente de Manterola, Magistral Canon of the Holy Cathedral Church of Vitoria and Curate of that church of San Andrés in this said town, by virtue of authorisation granted by the Patriarch of the Indies, Military Vicar General and Senior Chaplain Priest of the Royal Palace, in a decree of 9 March, I solemnly administered the Holy Sacrament of Baptism to María Luisa Enriqueta Josefina, who was born in Madrid on April 4 of 1868, at one in the afternoon, and that the same day she was baptized by Dr. Gabriel de Usera y Alarcón, now deceased, as daughter of Don Enrique Pío María Francisco de Paula Luis Antonio de Borbón y de Castellví, Duke of Seville, and Doña Josefina Paradé y Libié; the first from Toulouse and the second from Argelés, both in the Kingdom of France; the paternal granddaughter of HRH Infante Enrique of Spain and Her Excellency Doña Elena de Castellví, Duchess of Seville; and on the maternal side, Messrs. D. Juan and Doña Genoveva; Her godfather was the Presbyter Pedro Lumbreras, Senior Lieutenant of the priest of this church, to whom I warned of the spiritual kinship and other obligations, and as witness was José Díaz y León; and I sign this, Vicente de Manterolas." María Luisa further countered her mother's allegations by submitting that she was indeed born in 1868 at Madrid, and not in 1863 at Paris. María Luisa noted her father's affection for her, and her mother's disdain for her after the birth of her sister Marta. María Luisa also submitted a letter from her father, which read: "My very dear daughter: Although in five days I will have the pleasure of hugging you, I want you to receive my thoughts tomorrow as proof of the true affection that I profess for you on the occasion of tomorrow, the 4th of April, being the anniversary of your birth. You are eleven years old, and I pray to God that for long and happy years I may receive your sweet caresses and tender hugs. I will write to you before I go to look for you, and I will finish today because of how busy I am. Receive a thousand hugs from your father, who always loves you the same. Enrique. Bordeaux 3 April 1879."

Josefina countered her eldest daughter's evidence by claiming that María Luisa had indeed been born on 4 April 1863 at Paris to Josefina, who had given her the name Maria Paulina. Josefina alleged that María Luisa had then been taken care of by an aunt of Josefina. Ultimately, the court ruled (1) that María Luisa was born in 1868 as the natural daughter of Enrique and Josefina, (2) that María Luisa had been subsequently legitimised by her parents' marriage in 1870, and (3) that María Luisa had the right to succeed to her father's title.

In 1908, María Luisa and her husband Juan left their residence in Barcelona and took a house in London and a country house in Sussex. María Luisa was more commonly referred to as Marie Louise in the British press; she was also often accorded the style of Royal Highness and the title Princess of Bourbon - neither of which she legally possessed. The Duchess of Seville and her husband quickly joined and were accepted by British high society. In December 1911, the Duke Consort of Seville underwent a serious operation in London; Juan spent his recovery in a nursing home. In May 1914, several works of Pablo Antonio Béjar Novella, a painter for Spanish royals, were unveiled at Welbeck Gardens: the subjects of his brush were Queen Victoria Eugenia of Spain, the Ambassadress of Spain, and the Duchess of Seville. The exhibition was visited by King Manoel II of Portugal with his mother Queen Amélie as well as Princess Beatrice of Battenberg. Juan, Duke of Seville, joined the British war effort during World War I and served as a private in the Coldstream Guards. He was wounded in Rochdale, France, in December 1915. In April 1916, María Luisa met then-Crown Prince Alexander of Serbia (later King Alexander I of Yugoslavia) during a visit that Alexander made to London to increase awareness of the Serbian military efforts during the Great War. On 13 December 1918 in Shropshire, Juan Monclús y Cabanellas, Duke of Seville, died following an operation; he was fifty-six years-old. María Luisa was now a widow; she and Juan did not have children.

|

| Enriqueta, Duchess of Seville. |

On 2 July 1919, María Luisa ceded the Duchy of Seville to her youngest sister, Enriqueta. Their middle sister Marta waived her rights of succession. In 1907, Enriqueta had married her first cousin Francisco de Bórbon de la Torre (1882-1952); the couple had three children, thus securing the future of the Duchy of Seville. Enriqueta's grandson is the current Duke of Seville.

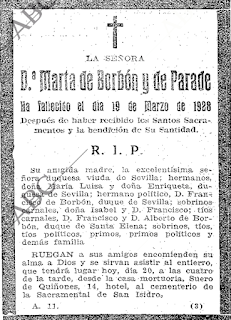

María Luisa's sister Marta died on 19 March 1928 in Madrid. Marta was forty-seven years-old. She had never married and left no children.

|

| Maria Luisa, Duquesa de Sevilla, in 1920. Photo (c) National Portrait Gallery. |

In July 1929, Mr Frederick Dempster-Smith, a late resident of the Hotel Victoria in London and the Imperial Hotel in Bournemouth, left £5,000 (modern equivalent being £221,777) to María Luisa. Mr Dempster-Smith gave this bequest whilst "begging Her Royal Highness's gracious acceptance of such a sum as a slight token of gratitude for her unvarying kindness, consideration, and sympathy to me and my family for so many years." At some point, María Luisa moved back to Spain. In July 1934, María Luisa was a guest of Mrs Maurice Clayton in London; it was her first visit back to the British capital since the Spanish Revolution. At the end of her stay, María Luisa returned to Barcelona.

|

| The death notice of Doña Josefina, Duquesa Viuda de Sevilla. |

On 20 October 1939, María Luisa's mother Josefina, Dowager Duchess of Seville, died in Madrid. Josefina was ninety-nine years-old. Despite the lengths at which the dowager duchess went to disinherit her eldest daughter, María Luisa was listed in Josefina's obituary as her daughter.

|

| A copy of the portrait of Maria Luisa by Pablo Antonio Béjar Novella. |

The life of Dona Isabel de Solís is a testament to the complexities of the Spanish aristocracy during the 15th and 16th centuries. Her story is a fascinating blend of love, power, and intrigue that continues to captivate historians and scholars to this day. As we delve into the intricacies of her life, it becomes clear that Dona Isabel de Solís was a woman of remarkable influence and strategic abilities, navigating the treacherous waters of Spanish politics with ease. Her life is a remarkable example of the influence women could wield in a society dominated by men, and her legacy continues to inspire and educate us about the rich cultural heritage of Spain.

As we conclude our exploration of the life of Dona Isabel de Solís, it is clear that her story is a powerful reminder of the enduring impact of women on history. Her life is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of women in the face of adversity, and her legacy continues to inspire and educate us about the importance of understanding and appreciating the contributions of women to our collective past. Whether you are a historian, a scholar, or simply someone interested in the fascinating stories of the past, the life of Dona Isabel de Solís is a compelling and thought-provoking tale that is sure to leave a lasting impression.

No comments:

Post a Comment